旅易小過

Journeying without Travelling or turning 56 into 62 [by changing the upper 陽 into 陰*]

旅途旅行

| 47 | 道德經: | 不出戶知天下;不闚牖見天道。 其出彌遠,其知彌少。 是以聖人不行而知,不見而名,不為而成。 |

47

旅 trip, brigade, travel, troops, force |

小過

- (archaic) minor slight; minor offence

- (education, etc.) minor offence; minor demerit

| 艮 Gèn Mountain | 33 Retiring | 15 Humbling | 62 Small Exceeding | 39 Limping | 52 Bound | 53 Infiltrating | 56 Sojourning | 31 Conjoining |

|---|

The story of Galahad and his quest for the Holy Grail is a relatively late addition to the Arthurian legend. Galahad does not feature in any romance by Chrétien de Troyes, or in Robert de Boron's Grail stories, or in any of the continuations of Chrétien's story of the mysterious castle of the Fisher King. He first appears in a 13th-century Old French Arthurian epic, the interconnected set of romances known as the Vulgate Cycle.

The original conception of Galahad, whose adult exploits are first recounted in the fourth book of the Vulgate Cycle, may derive from the mystical Cistercian Order. According to some interpreters, the philosophical inspiration of the celibate, otherworldly character of the monastic knight Galahad came from this monastic order set up by St. Bernard of Clairvaux.

The Cistercian-Bernardine concept of Catholic warrior asceticism that so distinguishes the character of Galahad also informs St. Bernard's projection of ideal chivalry in his work on the Knights Templar, the Liber ad milites templi de laude novae militiae. Significantly, in the narratives, Galahad is associated with a white shield with a vermilion cross, the very same emblem given to the Knights Templar by Pope Eugene III.

According to the 13th-century Old French Prose Lancelot (part of the Vulgate Cycle), "Galahad" was Lancelot's original name, but it was changed when he was a child. At his birth, therefore, Galahad is given his father's own original name. Merlin prophesies that Galahad will surpass his father in valour and be successful in his search for the Holy Grail. Pelles, Galahad's maternal grandfather¤, is portrayed as a descendant of Joseph of Arimathea's brother-in-law Bron also known as Galahad (Galaad), whose line had been entrusted with the Grail by Joseph.

G+אל [al/el/il] => Gal/Gallois/Gaulois/Gauls² (Latin: Galli; Ancient Greek: Γαλάται, Galátai) a group of Celtic peoples of Continental Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly from the 5th century BC to the 5th century AD). The area they originally inhabited was known as Gaul. Their Gaulish language forms the main branch of the Continental Celtic languages.

61/62/63**:

䷽ 小過: Galahad/Galaad/Gallad/Gilead

䷾ 既濟: Perceval (or Peredur (Welsh pronunciation: [pɛˈrɛdɨr]), Perceval, Parzival, Parsifal, etc.)

Many later works have two wounded "Grail Kings" who live in the same castle, a father and son (or grandfather and grandson). The more seriously wounded father stays in the castle, sustained by the Grail alone, while the more active son can meet with guests and go fishing. The father is called the Wounded King, the son named the Fisher King.

The Fisher King legends imply that he becomes unable to father or support any next generation to carry on after his death (a "thigh" wound has been interpreted by many scholars in Arthurian literature as a genital wound). There are slight hints in the early versions that his kingdom and lands suffer as he does, and modern scholars have suggested his impotence affecting the fertility of the land and reducing it to a barren wasteland.

The Lancelot-Grail (Vulgate) prose cycle includes a more elaborate history for the Fisher King. Many in his line are wounded for their failings, and the only two that survive to Arthur's day are the Wounded King, named Pellehan (Pellam of Listeneise in Malory), and the Fisher King, Pelles*. Pelles engineers the birth of Galahad by tricking Lancelot into bed with his daughter Elaine, and it is prophesied that Galahad will achieve the Grail and heal the Wasteland. Galahad, the knight prophesied to achieve the Holy Grail and heal the Maimed King, is conceived when Elaine gets Dame Brisen to use magic to trick Lancelot into thinking that he is coming to visit Guenever. So Lancelot sleeps with Elaine, thinking her Guenever, but flees when he realizes what he has done. Galahad is raised by his aunt in a convent, and when he is eighteen, comes to King Arthur's court and begins the Grail Quest. Only he, Percival, and Bors are virtuous enough to achieve the Grail and restore Pelles.

* A diminutive of the male given names Per, Pär or Peter.

From Middle Low German *pelle, whose existence is assured by the word’s prevalence in eastern dialects of German Low German (and East Central German). It was introduced there by Dutch settlers from Middle Dutch pelle, an old borrowing from Latin pellis (“skin”).

² The Gauls of Gallia Celtica, according to the testimony of Caesar, called themselves Celtae in their own language (as distinct from Belgae and Aquitani), and Galli in Latin. These names came to be applied more widely than their original sense, Celtae being the origin of the term Celts itself. (In its modern meaning, it refers to all populations speaking a language of the "Celtic" branch of Indo-European). Galli is the origin of the adjective Gallic, now referring to all of Gaul.

The English name Gaul was not derived from Latin Galli, but from the Germanic word *Walhaz. (see Gaul infra).

Despite the superficial similarity, the English term Gaul is unrelated to the Latin Gallia. It stems from the French Gaule, itself deriving from the Old Frankish *Walholant (via a Latinized form *Walula), literally the "Land of the Foreigners/Romans". *Walho- is a reflex of the Proto-Germanic *walhaz, "foreigner, Romanized person", an exonym applied by Germanic speakers to Celts and Latin-speaking people indiscriminately. It is cognate with the names Wales, Cornwall, Wallonia, and Wallachia. The Germanic w- is regularly rendered as gu- / g- in French (cf. guerre "war", garder "ward", Guillaume "William"), and the historic diphthong au is the regular outcome of al before a following consonant (cf. cheval ~ chevaux). French Gaule or Gaulle cannot be derived from Latin Gallia, since g would become j before a (cf. gamba > jambe), and the diphthong au would be unexplained; the regular outcome of Latin Gallia is Jaille in French, which is found in several western place names, such as, La Jaille-Yvon and Saint-Mars-la-Jaille. Proto-Germanic *walha is derived ultimately from the name of the Volcae.

Also unrelated, in spite of superficial similarity, is the name Gael. The Irish word gall did originally mean "a Gaul", i.e. an inhabitant of Gaul, but its meaning was later widened to "foreigner", to describe the Vikings, and later still the Normans. The dichotomic words gael and gall are sometimes used together for contrast, for instance in the 12th-century book Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib.

Celts, Celtae

The first recorded use of the name of Celts – as Κελτοί (Keltoí) – to refer to an ethnic group was by Hecataeus of Miletus, the Greek geographer, in 517 BCE when writing about a people living near Massilia (modern Marseille). In the 5th century BCE, Herodotus referred to Keltoi living around the head of the Danube and also in the far west of Europe.

The etymology of the term Keltoi is unclear. Possible origins include the Indo-European roots *ḱel, 'to cover or hide' (cf. Old Irish celid), *ḱel-, 'to heat', or *kel- 'to impel'. Several authors have supposed the term to be Celtic in origin, while others view it as a name coined by Greeks. Linguist Patrizia De Bernardo Stempel falls in the latter group; she suggests that it means "the tall ones".

The Romans preferred the name Gauls (Latin: Galli) for those Celts whom they first encountered in northern Italy (Cisalpine Gaul). In the 1st century BCE, Caesar referred to the Gauls as calling themselves "Celts" in their own tongue.

According to the 1st-century poet Parthenius of Nicaea, Celtus (Κελτός, Keltos) was the son of Heracles and Celtine (Κελτίνη, Keltine), the daughter of Bretannus (Βρεττανός, Brettanos); this literary genealogy exists nowhere else and was not connected with any known cult. Celtus became the eponymous ancestor of Celts. In Latin, Celta came in turn from Herodotus's word for the Gauls, Keltoi. The Romans used Celtae to refer to continental Gauls, but apparently not to Insular Celts. The latter are divided linguistically into Goidels and Brythons.

The name Celtiberi is used by Diodorus Siculus in the 1st century BCE, of a people whom he considered a mixture of Celtae and Iberi.

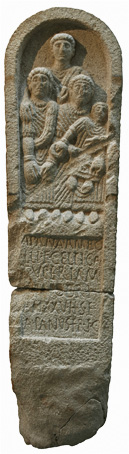

Celtici

Aside from the Celtiberians — Lusones, Titii, Arevaci, and Pellendones, among others – who inhabited large regions of central Spain, Greek and Roman geographers also spoke of a people or group of peoples called Celtici or Κελτικοί living in the south of modern-day Portugal, in the Alentejo region, between the Tagus and Guadiana rivers.[10] They are first mentioned by Strabo, who wrote that they were the most numerous people inhabiting that region. Later, Ptolemy referred to the Celtici inhabiting a more reduced territory, comprising the regions from Évora to Setúbal, i.e. the coastal and southern areas occupied by the Turdetani.

Pliny mentioned a second group of Celtici living in the region of Baeturia (northwestern Andalusia); he considered that they were "of the Celtiberians from the Lusitania, because of their religion, language, and because of the names of their cities".

In Galicia in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, another group of Celtici[12] dwelt along the coasts. They comprised several populi, including the Celtici proper: the Praestamarici south of the Tambre river (Tamaris), the Supertamarici north of it, and the Nerii by the Celtic promontory (Promunturium Celticum). Pomponius Mela affirmed that all inhabitants of Iberia's coastal regions, from the bays of southern Galicia to the Astures, were also Celtici: "All (this coast) is inhabited by the Celtici, except from the Douro river to the bays, where the Grovi dwelt (…) In the north coast first there are the Artabri, still of the Celtic people (Celticae gentis), and after them the Astures." He also wrote that the fabulous isles of tin, the Cassiterides, were situated among these Celtici.

The Celtici Supertarmarci have also left a number of inscriptions, as the Celtici Flavienses did. Several villages and rural parishes still bear the name Céltigos (from Latin Celticos) in Galicia. This is also the name of an archpriesthood of the Roman Catholic Church, a division of the archbishopric of Santiago de Compostela, encompassing part of the lands attributed to the Celtici Supertamarici by ancient authors.

Introduction in Early Modern literature

The name Celtae was revived in the learnèd literature of the Early Modern period. The French celtique and German celtisch first appear in the 16th century; the English word Celts is first attested in 1607. The adjective Celtic, formed after French celtique, appears a little later, in the mid-17th century. An early attestation is found in Milton's Paradise Lost (1667), in reference to the Insular Celts of antiquity: [the Ionian gods ... who] o'er the Celtic [fields] roamed the utmost Isles. (I.520, here in the 1674 spelling). Use of Celtic in the linguistic sense arises in the 18th century, in the work of Edward Lhuyd.

In the 18th century, the interest in "primitivism", which led to the idea of the "noble savage", brought a wave of enthusiasm for all things "Celtic." The antiquarian William Stukeley pictured a race of "ancient Britons" constructing the "temples of the Ancient Celts" such as Stonehenge (actually a pre-Celtic structure). In his 1733 book History of the Temples of the Ancient Celts, he recast the "Celts" "Druids".[20] James Macpherson's Ossian fables, which he claimed were ancient Scottish Gaelic poems that he had "translated," added to this romantic enthusiasm. The "Irish revival" came after the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 as a conscious attempt to promote an Irish national identity, which, with its counterparts in other countries, subsequently became known as the "Celtic Revival".

Pronunciation[edit]

The initial consonant of the English words Celt and Celtic is realised primarily as /k/ and occasionally /s/ in both modern UK standard English and American English, although /s/ was formerly the norm. In the oldest attested Greek form, and originally also in Latin, it was pronounced /k/, but a regular process of palatalisation around the first century CE changed /k/ → /s/ in later Latin whenever it appears before a front vowel like /e/. The pronunciation with /k/ was taken into German and /s/ French, and both pronunciations were taken into English at different times.

The English word originates in the 17th century. Until the mid-19th century, the sole pronunciation in English was /s/, in keeping with the inheritance of the letter ⟨c⟩ from Old French into Middle English. From the mid-19th century onward, academic publications advocated the variant with /k/ on the basis of a new understanding of the word's origins. The pronunciation with /s/ remained standard throughout the 19th to early 20th century, but /k/ gained ground during the later 20th century. A notable exception is that the /s/ pronunciation remains the most recognised form when it occurs in the names of sports teams, most notably Celtic Football Club in Scotland, and the Boston Celtics basketball team in the United States. The title of the Cavan newspaper The Anglo-Celt is also pronounced with the /s/.

Modern uses

In current usage, the terms "Celt" and "Celtic" can take several senses depending on context: the Celts of the European Iron Age, the group of Celtic-speaking peoples in historical linguistics, and the modern Celtic identity derived from the Romanticist Celtic Revival.

Linguistic context

After its use by Edward Lhuyd in 1707, the use of the word "Celtic" as an umbrella term for the pre-Roman peoples of the British Isles gained considerable popularity. Lhuyd was the first to recognise that the Irish, British, and Gaulish languages were related to one another, and the inclusion of the Insular Celts under the term "Celtic" from this time forward expresses this linguistic relationship. By the late 18th century, the Celtic languages were recognised as one branch within the larger Indo-European family.

Historiographical context

The Celts are an ethnolinguistic group of Iron Age European peoples, including the Gauls (including subgroups such as the Lepontians and the Galatians), the Celtiberians, and the Insular Celts.

The timeline of Celtic settlement in the British Isles is unclear and the object of much speculation, but it is clear that by the 1st century BCE most of Great Britain and Ireland was inhabited by Celtic-speaking peoples now known as the Insular Celts. These peoples were divided into two large groups, Brythonic (speaking "P-Celtic") and Goidelic (speaking "Q-Celtic.") The Brythonic groups under Roman rule were known in Latin as Britanni, while the use of the names Celtae or Galli/Galatai was restricted to the Gauls. There are no examples of text from Goidelic languages prior to the appearance of Primitive Irish inscriptions in the 4th century CE; however, there are earlier references to the Iverni (in Ptolemy c. 150, later also appearing as Hierni and Hiberni) and, by 314, to the Scoti.

Simon James argues that while the term "Celtic" expresses a valid linguistic connection, its use for both Insular and Continental Celtic cultures is misleading, as archaeology does not suggest a unified Celtic culture during the Iron Age.

Modern context

With the rise of Celtic nationalism in the early to mid-19th century, the term "Celtic" also came to be a self-designation used by proponents of a modern Celtic identity. Thus, in a discussion of "the word Celt," a contributor to The Celt states, "The Greeks called us Keltoi," expressing a position of ethnic essentialism that extends "we" to include both 19th-century Irish people and the Danubian Κελτοί of Herodotus. This sense of "Celtic" is preserved in its political sense in the Celtic nationalism of organisations such as the Celtic League, but it is also used in a more general and politically neutral sense in expressions such as "Celtic music."

Galli, Galatai

Latin Galli might be from an originally Celtic ethnic or tribal name, perhaps borrowed into Latin during the Gallic Wars. Its root may be the Common Celtic *galno-, meaning "power" or "strength." The Greek Γαλάται Galatai (cf. Galatia in Anatolia) seems to be based on the same root, borrowed directly from the same hypothetical Celtic source that gave us Galli (the suffix -atai simply indicates that the word is an ethnic name).

The linguist Stefan Schumacher presents a slightly different account: he states that Galli (nominative singular *Gallos) is derived from the present stem of the verb that he reconstructs for Proto-Celtic as *gal-nV- (the V indicating a vowel whose unclear identity does not permit full reconstruction). He writes that this verb means "to be able to, to gain control of," and that Galatai comes from the same root and is to be reconstructed as nominative singular *galatis < *gelH-ti-s. Schumacher gives the same meaning for both reconstructions, namely Machthaber, "potentate, ruler (even warlord)," or alternatively Plünderer, Räuber, "raider, looter, pillager, marauder"; and notes that if both names were exonyms, it would explain their pejorative meanings. The Proto-Indo-European verbal root in question is reconstructed by Schumacher as *gelH-, meaning Macht bekommen über, "to acquire power over," in the Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben.

Gallaeci

The name of the Gallaeci (earlier form Callaeci or Callaici), a Celtic federation in northwest Iberia, may seem related to Galli but is not. The Romans named the entire region north of the Douro, where the Castro culture existed, in honour of the Castro people who settled in the area of Calle – the Callaeci.

Gaul, Gaulish, Welsh

English Gaul / Gaulish are unrelated to Latin Gallia / Galli, despite their superficial similarity.

The English words ultimately stem from the reconstructed Proto-Germanic root *walhaz, "foreigner, Romanised person." During the early Germanic period, this exonym seems to have been applied broadly to the peasant population of the Roman Empire, most of whom lived in the areas being settled by the Germanic peoples; whether the peasants spoke Celtic or Latin did not matter.

The Germanic root likely made its way into French via Latinisation of Frankish Walholant "Gaul," literally "Land of the Foreigners." Germanic w is regularly rendered as gu / g in French (cf. guerre = war, garder = ward), and the diphthong au is the regular outcome of al before another consonant (cf. cheval ~ chevaux). Gaule or Gaulle can hardly be derived from Latin Gallia, since g would become j before a (cf. gamba > jambe), and the diphthong au would be unexplained. Note that the regular outcome of Latin Gallia in French is Jaille, which is found in several western placenames.

Similarly, French Gallois, "Welsh," originates not from Latin Galli but (with suffix substitution) from Proto-Germanic *walhisks "Celtic, Gallo-Roman, Romance" or from its Old English descendant wælisċ (= Modern English Welsh). Wælisċ originates from Proto-Germanic *walhiska-, "foreign" or "Celt" (South German Welsch(e) "Celtic speaker," "French speaker," "Italian speaker"; Old Norse valskr, pl. valir "Gaulish," "French,"). In Old French, the words gualeis, galois, and (Northern French) walois could refer to either Welsh or the Langue d'oïl. However, Northern French Waulle is first recorded in the 13th century to translate Latin Gallia, while gaulois is first recorded in the 15th century to translate Latin Gallus / Gallicus (see Gaul: Name).

The Proto-Germanic terms may ultimately have a Celtic root: Volcae, or Uolcae. The Volcae were a Celtic tribe who originally lived in southern Germany and then emigrated to Gaul; for two centuries they barred the southward expansion of the Germanic tribes. Most modern Celticists consider Uolcae to be related to Welsh gwalch, hawk, and perhaps more distantly to Latin falco (id.) The name would have initially appeared in Proto-Germanic as *wolk- and been changed by Grimm's Law into *walh-.

In the Middle Ages, territories with primarily Romance-speaking populations, such as France and Italy, were known in German as Welschland in contrast to Deutschland. The Proto-Germanic root word has also yielded Vlach, Wallachia, Walloon, and the second element in Cornwall. The surnames Wallace and Walsh are also cognates.

Gaels

The term Gael is, despite the superficial similarity, also completely unrelated to either Galli or Gaul.

The name ultimately derives from the Old Irish word Goídel. Lenition rendered the /d/ silent, though it still appears as ⟨dh⟩ in the orthography of the modern Gaelic languages": (Irish and Manx) Gaedheal or Gael, Scottish Gaelic Gàidheal. Compare also the modern linguistic term Goidelic.

Britanni

The Celtic-speaking people of Great Britain were known as Brittanni or Brittones in Latin and as Βρίττωνες in Greek. An earlier form was Pritani or Πρετ(τ)αν(ν)οί in Greek (as recorded by Pytheas in the 4th century BCE, among others, and surviving in Welsh as Prydain, the old name for Britain). Related to this is *Priteni, the reconstructed self-designation of the people later known as Picts, which is recorded later in Old Irish as Cruithin and Welsh as Prydyn.

Joseph of Arimathea

Giuseppe, Iosepes; Joseph d'Abarimathie, - d'Arimathie, - d'Arrimacie; Jospehe, Yosep

To the biblical data about him, romance adds the following. He was a soldier of Pilate who gave him the cup from the Last Supper. After the Resurrection, he was thrown into a dungeon where Jesus appeared to him and gave him the cup which had fallen out of his possession. After the fall of Jerusalem to Vespasian's army, he was set free and, with his sister Enygeus and her husband, Hebron or Brons*, went into exile with a group of fellow travellers. They began to suffer from a lack of food owing to sin, so they held a banquet. Those amongst the company who were not sinners were filled with the sweetness of the cup of Jesus, the Grail.

Brons and Enygeus had twelve sons, eleven of whom married. The twelfth, Alan, did not, so he was put in charge of his siblings, and they went out and preached Christianity. Brons was told to become a fisherman and was called the Rich Fisher. In Robert's version, Joseph entrusted the Grail to Brons but did not accompany him to Britain. Elsewhere, we are told that Joseph crossed to Britain on a miraculous shirt. We are also informed that he and his followers converted the city of Sarras, ruled by King Evelake who, having become a Christian, was able to defeat his enemy, King Tholomer. (According to the various sources, the city of Sarras is located either in the East (Asia), or else in Britain. It may have been thought of as the place from which the Saracens derived their name. It is not known outside romance.) John of Glastonbury claims that Joseph brought two cruets containing the blood and sweat of Jesus to Britain, but he does not mention the Grail.

So, Joseph of Arimathea was the disciple of Jesus. Josephe was Joseph's son, first bishop of Britain, miraculously consecrated by Christ Himself. Joseph is named in all four Gospels and are said to have donated his own new tomb outside Jerusalem to the body of Jesus. According to the tradition which Phyllis Ann Karr encountered orally and not in connection with the Arthurian cycle, Joseph first visited Britain with Jesus during the latter's hidden years before His public preaching; they came ashore on Cornwall.

After Christ's resurrection, Joseph and Josephe converted Nascien and Mordrains and their families and returned to Britain, bringing Christianity, the Holy Grail, the flowering thorn which Joseph planted at Glastonbury, and a number of followers, as described in detail in Volume I, Lestoire del Saint Graal, of the Vulgate.

Unlike Nascien and Mordrains, Joseph and Josephe did not miraculously survive into Arthur's times. Either Joseph or Josephe did, however, return to Carbonek Castle to celebrate the climactic mysteries of the Grail at a Mass attended by Galahad and his companions.

The romance Sone de Nausay says that Joseph drove the Saracens out of Norway, married the pagan king's daughter and became king himself. God made him powerless and the land became blighted. Fishing was his only pleasure and men came to call him the Fisher King. At last, he was cured by a knight. He provided for the foundation of the Grail Castle-cum-Monastery with thirteen monks, typifying Christ and his twelve apostles.

The interpolations of William of Malmesbury's History of Glastonbury say Joseph was sent to Britain by Saint Philip who was preaching in Gaul. With regard to Gaul, there is a tradition which says that, with Mary Magdalene, Lazarus, Martha and others, Joseph was placed in an oarless boat which was divinely guided to Marseilles. J.W. Taylor says there is an Aquitanian legend that says Joseph was one of a party which landed at Limoges in the first century and that there is a Spanish tale relating how Joseph, with Mary Magdalene, Lazarus and others, went to Aquitaine.

Taylor also cites a Breton tradition that Drennalus, first bishop of Treguier, was a disciple of Joseph. Taylor adduces these traditions as part of an attempt to show that Joseph came first to Gaul, then to Britain. It is worth noting, however, that the tradition of Mary Magdalene and Lazarus coming to Marseilles is not now regarded seriously by most hagiologists.

Joseph was said not only to have come to Britain but to have settled at Glastonbury where he was given land by King Arviragus. A local tradition, perhaps not older than the nineteenth century, says he buried the cup of the Last Supper above the spring in Glastonbury and hence the water has a red tinge. A tradition amongst certain metalworkers was that, sometime before the Crucifixion, Joseph actually brought Jesus and Mary to Cornwall. Benjamin suggests that Joseph may be identical with Joachim, the father of the Virgin Mary in the Protevangelium of James, an apocryphal work; but the two names are quite distinct in origin. In the Estoire Joseph is given a son, Josephe. In Sone de Nausay he had a son named Adam, while Coptic tradition claims he had a daughter, Saint Josa.

Galahad himself is called a direct descendant of Joseph; since both Pellam and Lancelot were descended from Joseph's convert Nascien, the relation would seem either to be spiritual, like that of a godparent and godchild or to have come through intermarriage between Nascien's male and Joseph's female descendants.

Josephe's cousin (Joseph's nephew?) Lucans first was appointed guardian of the ark containing the Grail, before Josephe reassigned the keepership of the holy vessel to Nascien's descendant Alain (or Helias) le Gros. Joseph's younger son Galahad, born after the arrival in Britain, becomes the direct ancestor of King Uriens.

Malory, or his editors, seem to know nothing of Josephe, ascribing some of his deeds (such as marking the Adventurous Shield) to Joseph.

A Jewish merchant and a member of the Sanhedrin. A supporter of Jesus, he arranged for the burial of Christ's body after the crucifixion. According to legend Joseph also acquired the chalice used by Jesus at the Last Supper and used this to catch Jesus' blood from the cross. This became the Holy Grail that Joseph later brought to Britain in around 63 AD when he established the first British Christian church at Glastonbury.

* The name חֶבְרוֹן Hebron: Summary

- Meaning

- Place Of Joining, Alliance

- Etymology

- From the verb חבר (habar), to join.

No comments:

Post a Comment