Why would I want to stimulate my vagus nerve?

How does feeling happier, improving digestion and reducing inflammation sound like?

When we activate the vagus nerve, we activate a part of our autonomic nervous system — which functions without our conscious awareness — called the parasympathetic system, aka relaxation response, or rest & digest state.

Conversely, the sympathetic system is associated with the fight or flight response and is activated in times of stress. Stress suppresses vagus nerve activation.

The vagus nerve has also been proposed to play a crucial role in the regulation of the immune response, also referred to as the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. This has huge implications in the treatment of many chronic health diseases involving the immune system and inflammation.

A poorly functioning vagus nerve has been associated with depression, panic disorders, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), irritable bowel syndrome, anxiety, epilepsy, fibromyalgia and dementia.

Research indicates that low vagal nerve tone alters the migrating motor complex in the gut, reducing gastrointestinal motility and thus allowing bacteria to flourish in the small intestine.. which can eventually lead to SIBO (Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth). So techniques to stimulate the vagus nerve should be an important part of any SIBO protocol.

GETting TO KNOW the VAGUS NERVE

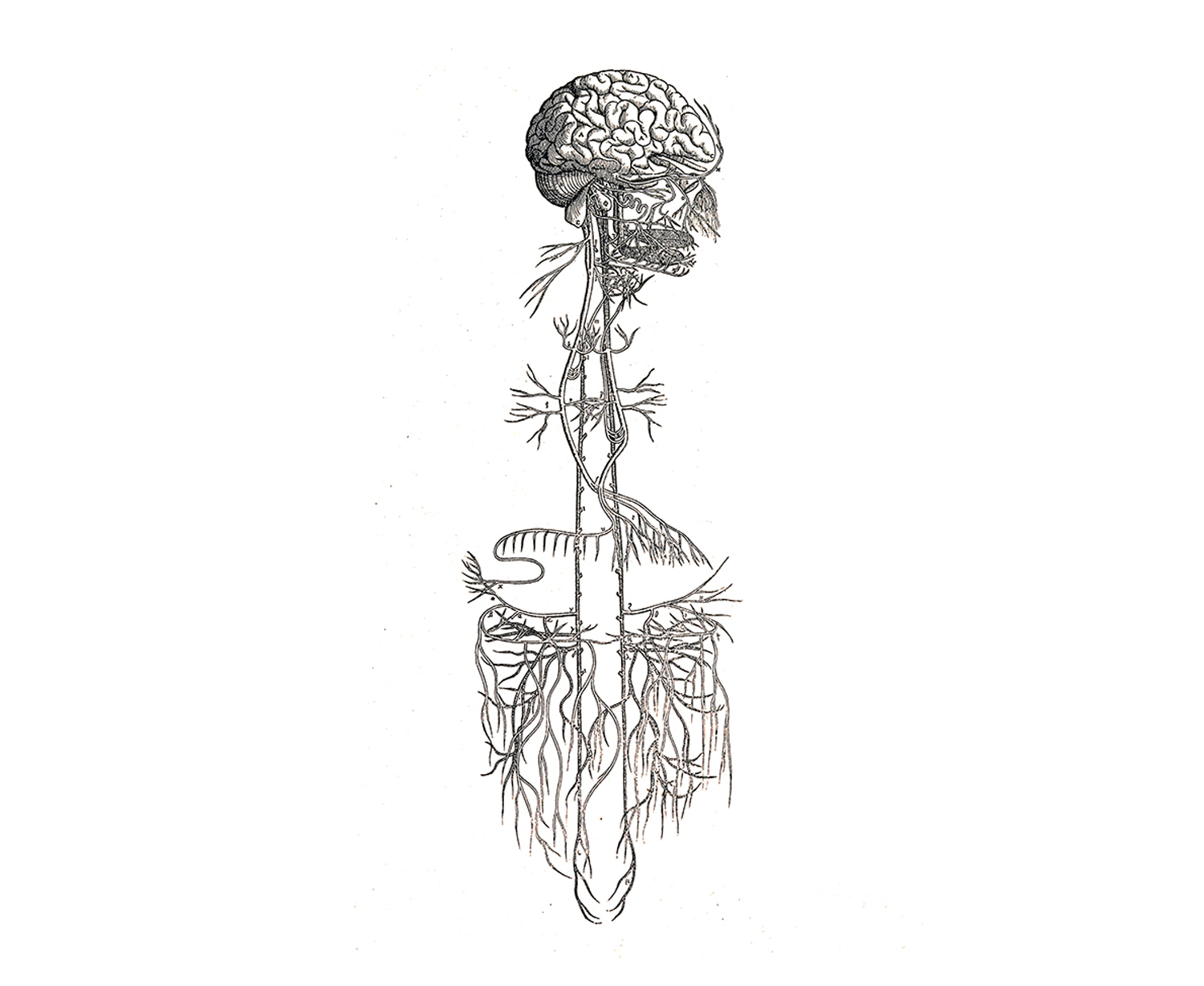

The vagus nerve serves as a communication pathway between the brain & the gut, sometimes referred to as the “brain-gut axis”. We may think of it as a bidirectional highway, consisting of afferent fibres (going down to the organs) and efferent fibres (going up to the brain).

Vagus is the Latin term for “wandering”. The name alludes to the complexity of connections that the branches of this nerve form within the body.

It is the 10th cranial nerve (Nerve X) and is the body’s longest nerve. It starts in the brainstem, just behind the ears.

It is composed of afferent sensory fibres (about 80%) and efferent motor fibres (about 20%).

The efferent fibres travel down each side of the neck, extending from the brainstem down into our stomach & intestines, enervating our heart & lungs, and connecting our throat & facial muscles. It has an effect on our immune cells, organs and tissues.

However, most of the vagus nerve’s fibres are actually afferent fibres and carries sensory information from the organs back to the brain. Through these afferent fibres, the vagus nerve is able to sense the microbiota metabolites and to transfer this gut information to the central nervous system. This is one of the ways our gut bacteria influence how we feel fascinating.

The vagus nerve is a key player in the body-mind connection; it’s behind your gut instinct, the knot in your throat, and the sparkle in your smile.

MEASURING my VAGAL TONE

The strength of our Vagus response is known as our vagal tone and it can be determined by measuring our Heart Rate Variability (HRV).

Every time we breathe in, our heart beats faster in order to speed the flow of oxygenated blood around our body. Breathe out and our heart rate slows. This variability is one of many things regulated by the Vagus nerve, which is active when we breathe out but suppressed when we breathe in, so the bigger our difference in heart rate when breathing in and out, the higher our vagal tone.

However, it’s important to note that this only measures the heart innervation of the vagus nerve, and so it is not 100% accurate. In other words, high HRV does not necessarily mean that we have no dysfunction in the vagus nerve. Still, it is a very useful measure though.

➥This is one of them: http://www.emwave.com.au/emwave_2.html

WHEN I INCREASE my VAGAL TONe

- It increases gut flow/gut motility (aka peristalsis & migrating motor complex).

- It stimulates digestive juices and bile release (hence killer digestion!)

- It keeps your immune system in check (less cold and flu, and potentially less auto-immunity).

- It reduces inflammation throughout the body, through its role in the anti-inflammatory pathway.

- It has a positive impact on an assortment of ‘happy’ hormones and enzymes such as endorphins, acetylcholine and oxytocin, which bring about positive feelings in the body and reduce the sensation of pain.

- Research indicates that a healthy Vagus nerve is vital in experiencing empathy and fostering social bonding, and it is crucial to our ability to observe, perceive, and make complex decisions. So people with high vagal tone are not just healthier, they’re also socially and psychologically stronger – better able to concentrate and remember things, happier and less likely to be depressed, more empathetic and more likely to have close friendships.

LOW VAGAL TONE & INFLAMMATION

We all know that chronic inflammation has devastating effects on the body and can cause a host of chronic diseases, including digestive diseases, chronic fatigue syndrome, depression, autoimmune diseases, etc.

Well, guess what is associated with chronic inflammation: that is right, low vagal tone.

One of the Vagus nerve’s job is to reset the immune system and switch off the production of proteins that fuel inflammation. Low vagal tone means this regulation is less effective and inflammation can become excessive.

VAGUS NERVE STIMULATION & DIGESTION

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) increases gastrin and hydrochloric acid production in the stomach and increases oesophageal/gastric motility = improves digestion and enzyme release.

VNS causes closure of intestinal tight junctions (hence reducing leaky gut symptoms).

VNS stimulate the migrating motor complex, helping in the treatment of SIBO, and perhaps more importantly, prevention of recurrence.

10 WAYS TO STIMULATE the VAGAL TONE

The Vagus nerve passes through the belly, diaphragm, lungs, throat, inner ear, and facial muscles.

Therefore, practices that change or control the actions of these areas of the body can influence the functioning of the Vagus nerve through the mind-body feedback loop.

1- Singing/ humming/chanting. The Vagus nerve passes through the vocal cords and the inner ear and the vibrations of humming is a free and easy way to influence our nervous system states. In yoga, this is often done by chanting the sound ॐ. Bee breath exercise is another way to achieve this.

2- Breathing exercises. Of all the various functions of our autonomic nervous systems, from heartbeat, perspiration, hormonal release, gastrointestinal operation, neurotransmitter secretion, etc., the breath stands alone as the only subsystem the conscious mind can put into ‘manual override’.

Long deep breathing is an excellent way to get out of the fight or flight response.

- Belly breathing.

- Lengthening the exhale

- Ujjayi breath: I can further stimulate the Vagus nerve by creating a slight constriction at the back of the throat & creating an “ahh”. I should breathe as if I was trying to fog a mirror to create the feeling in the throat, but keeping my mouth close and breathe in and out through the nostrils.

3- Meditation. Meditation, especially loving-kindness meditation which promotes feelings of goodwill towards yourself and others. A 2010 study found that increasing positive emotions led to increased social closeness and an improvement in vagal tone.

The presence of healthy bacteria in the gut creates a positive feedback loop through the Vagus nerve, increasing its tone.

The Vagus nerve essentially reads the gut microbiome and initiates a response to modulate inflammation based on whether or not it detects pathogenic versus non-pathogenic organisms. In this way, the gut microbiome can have an effect on your mood, stress levels and overall inflammation.

5- Diving Reflex.

Considered a first-rate Vagus nerve stimulation technique, splashing cold water on the face from the lips to the scalp line stimulates the diving reflex. Ideally, one would want to submerge the face in cold water for about 3 minutes. The diving reflex slows the heart rate, increases blood flow to the brain, reduces anger and relaxes the body. An additional technique that stimulates the diving reflex is to submerge the tongue in a liquid. Drinking & holding lukewarm water in the mouth, sensing the water with the tongue.

6- Gargling.

This technique was made popular by Dr Kharrazian and involves gargling for a few minutes until tears come into your eyes. This can be difficult at first, especially if the case of a weak vagal tone, so start with a short time and build up slowly. Ideally, the gargling should be done for up to 5 minutes, 3 times per day. It works again by activating the throat area and is described as doing “sprints” for the Vagus nerve.

7- Gagging.

Similar to gargling, but this time involves using a tongue depressor to activate the gag reflex. To be repeated 5 to 10 times, 3 times/day. This one is described as doing “push-ups” for the Vagus nerve.

8- Coffee enema.

Expanding the bowel increases Vagus nerve activation and caffeine increases bowel flow when having a coffee enema. This is especially useful if one tries to hold it for as long as possible. This will be difficult at first, especially with a weak vagal tone, but it will get easier with time. Coffee enemas can be fantastic for people suffering from constipation.

9- Connections & having fun

Reach out for relationships. Healthy connections to others, whether this occurs in a person, over the phone — or even via texts or social media in our modern world— can initiate regulation of our body and mind. Relationships can evoke the spirit of playfulness and creativity or can relax us into a trusting bond with another.

10- Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation, or TaVNS.

This is a way to electrically stimulate the vagus nerve via the ear and is probably the most effective overall.

The vagus nerve is involved in nearly every physiological action in the human body and harnessing its power can have an immediate and dramatic impact on your well-being.

- The superhighway of the body, transporting vital information between the brain and the rest of the internal organs;

- A symphony conductor, directing how fast or slow, loud or quiet the nervous system will be at any given time;

- Air traffic control, monitoring a multitude of moving parts to make sure all of the physiological aeroplanes fly safely & efficiently to their destination.

- In a time when we all speak the universal language of hyperbole, it would be easy to dismiss this vagus talk as just another passing trend from a wellness culture that promotes and discards the next! big! thing! for sport. (Literally.)

But, here’s the deal. Physicians as far back as the Roman Empire1 have been grappling with how the vagus nerve impacts bodily function. We have now learned that simple movement & breath exercises can be done at home to manually stimulate the vagus nerve in times of stress to trigger the body’s natural relaxation response. And for patients with conditions ranging from epilepsy to rheumatoid arthritis to Crohn’s disease, electronic vagus nerve stimulation is offering hope and showing long-term results. The power of the vagus nerve lies in its ability to impact physical and emotional conditions that have proven to be difficult to treat with traditional drug and medical interventions. When people run out of options—for medical disorders or stress management— they find their way to the vagus and realize the power this one part of our anatomy has over the entire system.

The hype is now consensus; the future of medicine and self-care will be interwoven with our understanding of the vagus nerve and how it works.

But First, What is the Vagus Nerve?

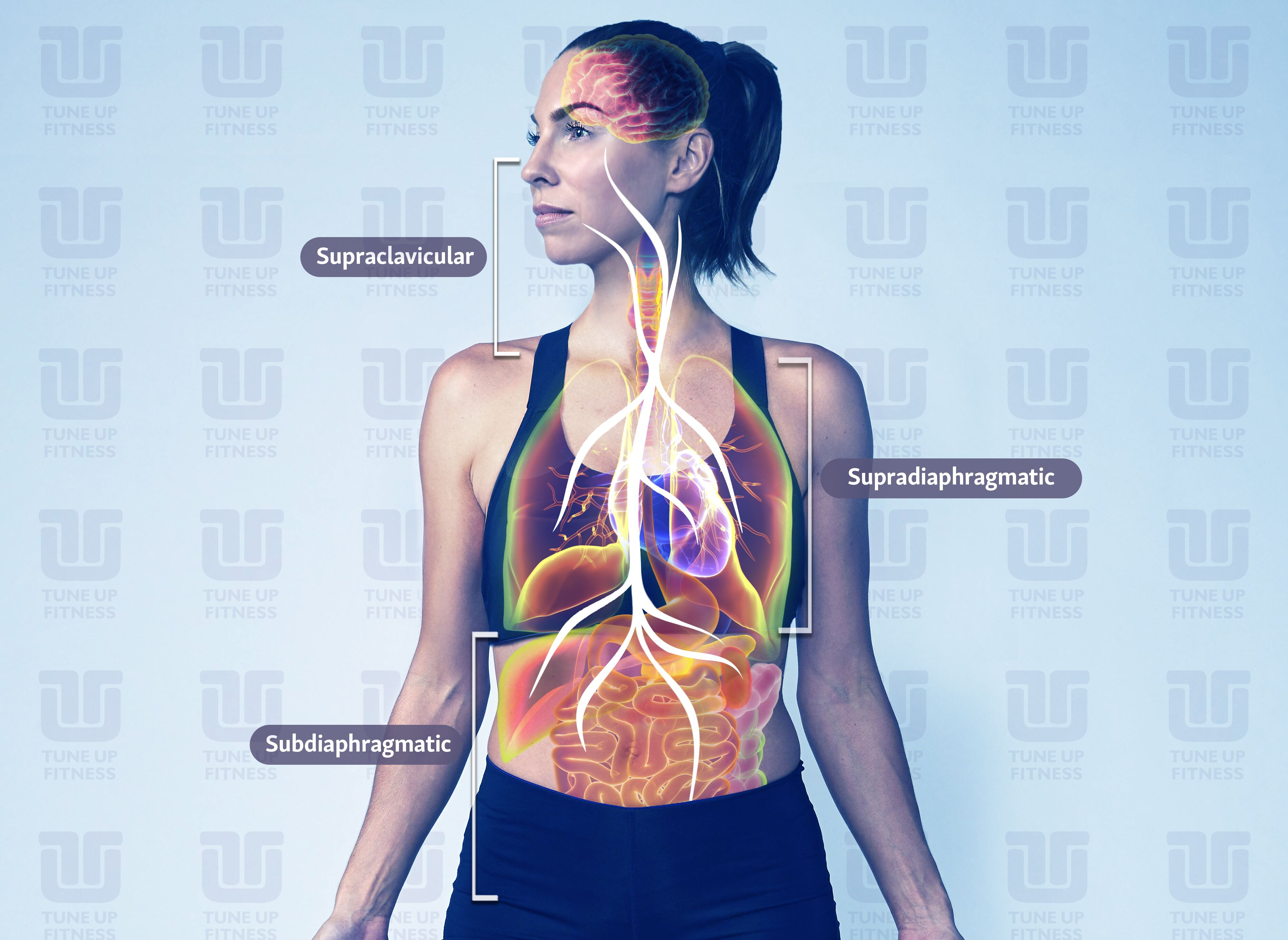

The vagus is the tenth cranial nerve, originating in the brain stem & travelling through the face, neck, lungs, heart, diaphragm and abdomen, including the stomach, spleen, intestines, colon, liver, and kidneys.2 Vagus is Latin for “wanderer,” an appropriate name for the longest cranial nerve in the body. The vagus nerve is intricately connected to mood, immune response, digestion, and heart rate.3

Why is everyone talking about the vagus nerve right now?

Now that it’s on my radar, I have started to notice it everywhere, from podcasts to Facebook groups to mainstream news articles. Marriage and Family Therapist Justin Sunseri launched The Polyvagal Podcast, a show about all things vagus nerve, in February of 2019 and quickly built an audience of thousands each month alongside his co-host Mercedes Corona. “I felt a compulsion to do it,” says Sunseri. “I literally woke up one night at four in the morning and the words Polyvagal Podcast were pounding in my head. I knew the information would be really good, but I had no idea what the bigger picture would be.”

Lisa Elliott is an aerial acrobat in Seattle who discovered the vagus nerve after a near-death experience from an aortic dissection. She started the Vagus Nerve Study Group in her living room with six friends in 2015, and it has morphed into a thriving Facebook community with almost nine thousand members studying the vagus together. “When I first started studying it, I was interested in the vagus nerve as a discrete anatomical structure,” says Elliott. “What is this thing that can make a big difference in chronic illnesses? But over the years, I came to see it as an anatomical map that can lead us to a new way of thinking about our bodies and beings, our emotions, and our interaction with the environment.”

Electronic Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS)

On the medical front, Dr Kevin Tracey is a neurosurgeon who has done groundbreaking work in the field of bioelectric, where a small electronic device is implanted under the skin of a patient’s chest to send electrical impulses to the vagus. He published a study in 20024 about mice with strokes, revealing that vagus nerve stimulation turned off the body’s production of tumour necrosis factor (TNF), a molecule produced by the immune system during an inflammatory response that, when regulated, is good for the body, but in excess can damage organs, cause blood pressure to drop, and lead to septic shock.5 This prompted a clinical trial using VNS on rheumatoid arthritis patients6 with high levels of TNF that caused debilitating pain. At the end of the forty-two-day study, the TNF levels of study participants were nearly the same as non-arthritic patients. Their pain was almost gone, joint swelling was reduced, and mobility had returned. Dr Tracey has also had success with Crohn’s disease patients and sees a future when diseases like Alzheimer’s, cancer, diabetes, and hypertension can be treated with bioelectronics. VNS has been approved by the FDA to treat epilepsy since 1997, and depression since 2005, but everything else right now is in the clinical trial stages. In addition to Dr Tracey’s work, there are studies being done on the impact of VNS on diabetes, stroke recovery, glucose metabolism, and many others around the world.

While researchers and the medical establishment wade through lengthy clinical trials and FDA approval processes, the good news is that it doesn’t require a surgical implant to impact your vagus nerve.

Manual Stimulation of the Vagus Nerve

Physical therapist & functional manual therapist Gregg Johnson uses his hands to do manual work on the vagus and trains other practitioners to do the same at his Institute of Physical Art in Colorado. He has been a physical therapist for fifty years but stumbled into an interest in the vagus nerve five years ago when he had a student who had high blood pressure and an elevated heart rate and was looking for a way to avoid going on long-term medication. Johnson palpated (examined with his hands) the neck, and could feel that the vagus nerve was in tension. “This was the first time I had selectively, consciously palpated the vagus nerve,” says Johnson. “All of a sudden, as everything started enhancing in mobility, his heart rate normalized and he started feeling like he hadn’t for months. And that night when he tested his blood pressure it had returned to normal.” Since then, Johnson has used manual vagus nerve stimulation to help patients with irritable bowel syndrome, kidney problems, and fertility issues, just to name a few.

Palpate: to examine a part of the body by touch for medical purposes

Myofascial self-massage shows both manual hand and soft-tool palpation.

There are a number of things you can do with breath and movement on your own at home to manually stimulate the vagus nerve. But to understand how first it helps to understand a little bit more about the anatomy and function of the vagus nerve itself.

Vagus Nerve Function

The vagus nerve is part of the autonomic nervous system, the body’s unconscious control system that helps regulate our internal organs to optimize health, growth, and restoration, a concept known as homeostasis.7 The autonomic nervous system is divided into two branches— the sympathetic branch, which mobilizes us for action (the “on” switch); and the parasympathetic branch, often referred to as the rest-and-digest state (the “off” switch). The vagus nerve resides in the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system. Much of our understanding of how the vagus functions within the parasympathetic branch, and our ability to impact it through breath and movement, can be traced to Dr Stephen Porges and the introduction of his Polyvagal Theory in 1994.

JARGON ALERT

Autonomic Nervous System: the part of the nervous system that unconsciously controls bodily function, including things like heart rate, breathing, and digestion. There are two branches of the Autonomic Nervous System:

- Sympathetic: your body’s ON switch, supporting mobilization for action

- Parasympathetic: your body’s OFF switch, supporting relaxation

The Polyvagal Theory

The Dorsal Complex & Shutdown

Dr Porges identified two pathways of the vagus nerve. The first pathway, the dorsal complex, is leftover from our pre-mammalian, ancient vertebrate ancestors. It’s often called the sub-diaphragmatic branch of the vagus, because it originates in the brain stem and supplies nerves to the visceral organs below the diaphragm, including the stomach, liver, spleen, kidneys, gallbladder, urinary bladder, small intestine, pancreas, and ascending and transverse parts of the colon.8 It is unmyelinated, which means it lacks a myelin (fatty) sheath and consequently transmits information slower than a nerve that is myelinated. When humans or other mammals sense they are in grave danger, a surge in dorsal activity can result in system shutdown, including a drop in blood pressure, with a potential for fainting or a state of shock.9 The dorsal vagal response is referred to in shorthand as shutdown.

The Ventral Complex and Safety

The second pathway of the vagus nerve is the ventral complex. It formed as we evolved from ancient reptiles to mammals and originates in the brain stem in the nucleus ambiguous, a group of motor neurons connected to the muscles integral to speech and swallowing, such as the soft palate, pharynx, and larynx.10 The ventral vagus is the primary regulator of the heart rate and muscles in the face and head. This newer ventral vagal path is myelinated and transmits information much faster than the dorsal vagal path. It is what is commonly referred to as our safe and social state and evolved to provide a social engagement system that was necessary in order for mammals to coexist, work in the community and reproduce. People in a ventral vagal state are generally engaged in the world, and open to connecting and cooperating with others.

Between the development of the dorsal vagal path & ventral vagal path, the sympathetic branch of the nervous system formed, allowing for mobilization in times of stress. This is most often referred to as the fight-or-flight reaction.

JARGON ALERT

Polyvagal Theory

Polyvagal Theory identifies how these three neural (of or relating to nerves or the nervous system) circuits — the dorsal vagal, sympathetic, and ventral vagal — are involved in evaluating our environment and reacting to cues of safety or threat. There are three organizing principles of the polyvagal theory11:

Hierarchy

The autonomic nervous system responds to cues in the environment in a specified and predictable way. Either in order from the oldest to newest neural circuits (dorsal, sympathetic, ventral), or the newest to oldest (ventral, sympathetic, dorsal).

Neuroception

This is a concept coined by Dr Porges that describes how our autonomic nervous system subconsciously evaluates & responds to cues of safety or danger in our environment. “Detection without awareness,” Dr Porges says. The vagus has more than 100,000 nerve fibres and communicates bidirectionally between the brain and the body, with 80% of the fibres communicating from the body to the brain, and the other 20% communicating from the brain to the body.12 So, that “gut feeling” we have felt before— that is neuroception. It is our body having what amounts to a “sixth sense” moment and communicating that information to our brain.

Co-regulation

This is the mutual regulation of the physiological state between individuals.13 One example Dr Porges uses for co-regulation is the relationship between a mother and her baby. If a mother is calming her child and the child responds by relaxing and vocalizing sounds of contentment, this has a reciprocal effect of calming the mother. If the infant continues to be upset and does not respond to the mother’s attempt to settle her, the mother will also get upset. Dr Porges calls this our “biological need to connect.”

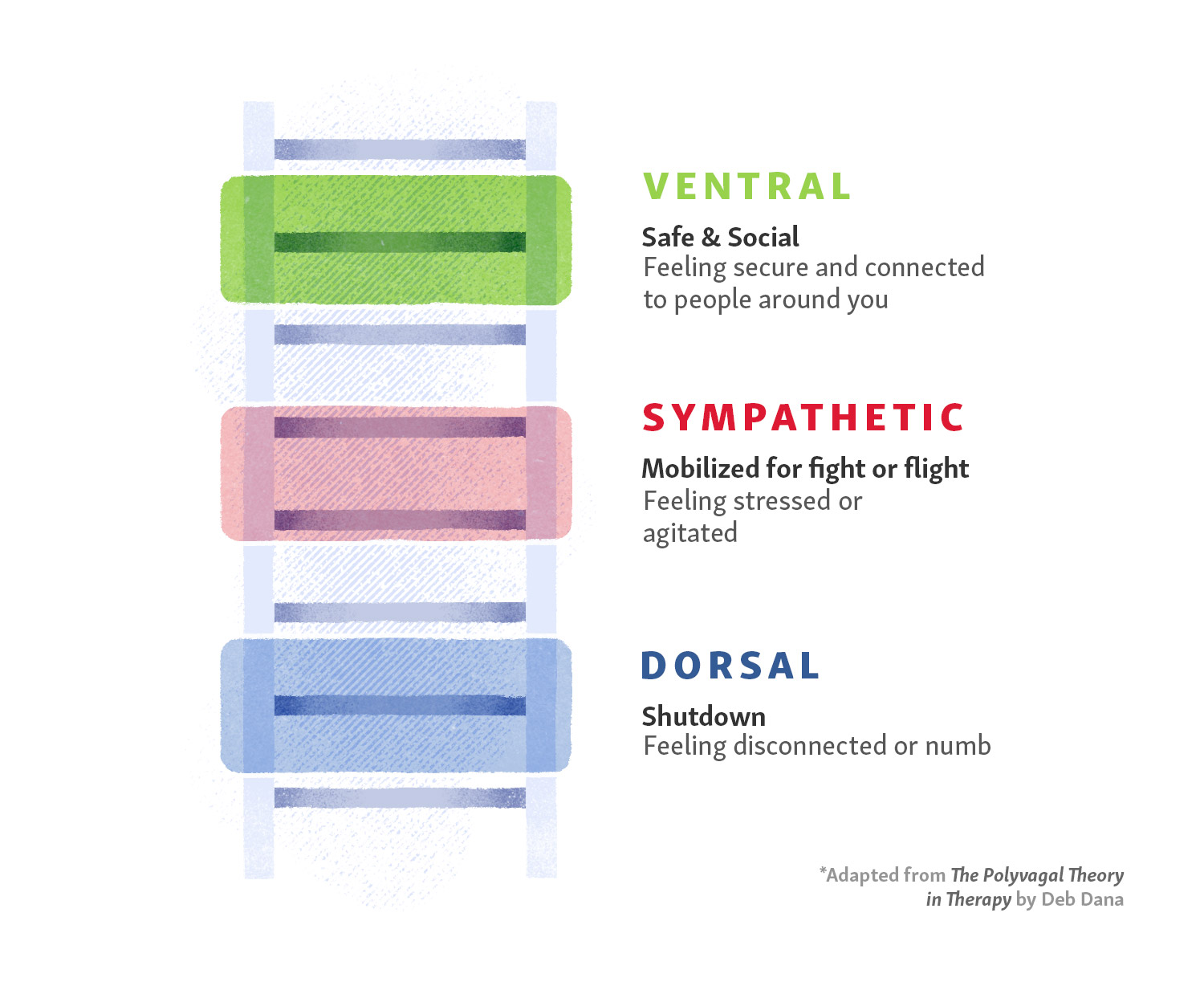

The Polyvagal Ladder

Deb Dana, the author of the book The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy, created the concept of the polyvagal ladder as a visual metaphor for how we experience physiological change as we move through the three neural circuits of the autonomic nervous system.

Ventral Vagus

At the top of the ladder is the ventral vagus, where the feelings are likely to be safety, comfort and engagement in the world around us. We generally feel content, mostly lacking in acute worry about anything.

Sympathetic

Just below the ventral vagus on the ladder is the sympathetic state, the place we move to for mobilization if we detect risk. This could be something relatively small, like receiving a vague email request for a meeting from a boss that causes us to wonder if we have done something wrong, or something as frightening as hearing a window break in the house in the middle of the night and worrying that we are about to become a victim of a home invasion. In both cases, our heart may start beating faster, our palms might sweat, and our mind may race as we worry about what could happen next.

Dorsal Vagus

At the bottom of the ladder is the dorsal vagus, where shutdown occurs. In the example of the email from a boss, if it turns out we were called into the office and fired, we would likely move down the ladder from sympathetic to dorsal state, and shutdown might look like extreme sadness or a bout of depression. In the broken window example, if it became clear quickly that we are about to be a victim of a home invasion, the shutdown could involve fainting or going into shock as a way for the body to protect us from a potentially catastrophic physical confrontation.

In both instances, it is possible to move up the polyvagal ladder instead of down, depending on the circumstance. In the example of the email, if we went to the meeting with a boss in a sympathetic state, heart racing and palms sweating, and it turns out it was a minor request about a project, we could quickly move back up the ladder into the safe and social ventral state, relieved that our fears about being fired were misplaced. And the same is true in the broken window example. If we discover it was not a broken window after all, but instead, a television that was left on with the volume up very loud, we would likely bounce quickly up the ladder to the ventral vagus, relieved that we and our family are not in danger after all.

The hybrid States of the Polyvagal Ladder

There are scenarios where two of the three neural states are combined. Stanley Rosenberg, the author of Accessing the Healing Power of the Vagus Nerve, calls these “hybrid states.”14 The fourth state combines the ventral vagal (safe & social) and sympathetic (mobilization) to create mobilization without fear. Examples of this might be going to a Zumba class, playing tag with our kids, or engaging in a friendly competition on the basketball court with friends. The fifth state combines the ventral vagal (safe & social) with the dorsal vagal (shutdown) to create immobilization without fear. This creates a feeling of calm and safety, and examples could include lying still with a trusted partner after intimacy or cuddling with our sleepy child before bedtime.

If we are stuck in a dorsal state and feel like we do not have any get-up-and-go, the breath can help.

How To Move Between States With Breath

Unless we are in a hybrid state like the examples mentioned above, which includes the safe & social feelings of the ventral vagus complex, being stuck in a sympathetic (fight-or-flight) or dorsal (shutdown) state can be draining to maintain — mentally, emotionally and physically. If we are locked in a sympathetic state, we might feel like we are constantly stressed, always waiting for another metaphorical shoe to drop. If we are locked in a dorsal state, we may find ourselves in a perpetual malaise, unable to meaningfully engage with the people in our life the world around us.

Luckily, there is a readily available way to move up the polyvagal ladder to include the safe & social feelings of the ventral state, and it starts with our breath. “The simplest vagal stimulation that you can recruit is being able to exhale slowly,” says Dr Stephen Porges. Stimulating the vagus nerve with slow exhales slows down the heart rate and gives our body cues of safety. “In the brain stem there is actually kind of like a switch,” continues Porges. “It is like a hot water/cold water option on the same knob. When we exhale, the vagal influences on our heart’s pacemaker get optimized. When we inhale, our heart rate goes up. And when we exhale, our heart rate goes down. If we spend more of our time exhaling, we calm our body down. If we shift rations so that most of the time we are inhaling, we are hyperventilating. We are huffing & puffing. When we see anxious people, they are inhaling virtually with every sentence or every word. They’re huffing and puffing.”

TuneUp Fitness founder Jill Miller designed an entire immersion program, Breath & Bliss, around the polyvagal theory, using breathwork, position, movement, community and a soft, air-filled sponge ball to manually stimulate the vagus nerve and give students tools to move out of a fight-or-flight or shutdown state. “I want people to feel like they have as many options as possible to be able to modulate their own state,” says Miller. “And to understand the ‘why’ really helps with the experience of it. My bias is that I believe once we know that we can shift our physiology and we train ourselves to witness our physiological shifts, it becomes a richer experience and we do not feel so victimized by our moods or reaction to things. I want empowered recovery to be in everyone’s toolkit.”

Breath & Bliss is a movement & breath-based approach that leans into Porges’s theory of how we respond to our environment and uses that knowledge for guidance on getting ourselves to a state where we can feel safe with ourselves and in the company of others. “One attribute of being a human being is that our body reacts to threat,” says Porges. “But it does not just react to threat, it transforms how we interact with other people. So we have to understand that our body is shifting states to try and take good care of us, but in doing that, it distorts how we see the world. We know that our bodies change states and promote certain attributes to protect us. The issue is, can we create the structure and context for our bodies to feel welcoming enough to bring other people into our world? Can we give up our chronic need to be defensive, to take a chance to be accessible and live with our own vulnerability?”

Senior Tune-Up Fitness® Instructor Lisa Hebert leads the Breath & Bliss Immersion internationally and has seen it transform students as they learn how to move between states. “I think the beauty of the polyvagal theory is that it brings us back to basics,” says Hebert. “Social interaction, human touch, human connection, a caring voice. All of these things we know so innately when we have a baby in our arms, but we grow up and push all that away so we can get tough and do everything ourselves. So we may lose it temporarily, but it’s this innate knowledge that we have in our gut somewhere.”

Hebert has also done Breath & Bliss work with first responders and former military members with PTSD. Jason Burd was a firefighter in Canada who almost died when a roof collapsed during a rescue operation in 2006. After the accident he went back to work, but suffered a back injury in 2010, followed by a lung injury in 2011. He ended his career as a firefighter because of physical pain, PTSD, and suicidal thoughts. He did Breath & Bliss with Hebert, where he learned breathing exercises and rolling techniques to stimulate the vagus nerve with the Courageous ball. “There were so many lightbulb moments,” says Hurd. “I realized that my recovery is in my hands. When I came home after the first day of the course I told my wife that I felt like the inside of my neck was bigger. My ability to breathe felt completely different. Now I use the Courageous ball a minimum of once a day, usually twice.”

Hurd’s experience is an example of how tuning in to breathing and manually stimulating our own vagus nerve, can result in a powerful shift from chronic pain and fight-or-flight anxiety, to empowered recovery.

“That is what I call embodiment,” says Miller. “It is when someone feels their way through their body, engaging in a conscious dialogue of their senses, feelings, urges and needs. Be willing to respond and parent ourselves with curiosity and support.”

According to Dr Porges, understanding polyvagal theory can help us negotiate with our bodies to optimize our experiences. “Amazingly, when we become more aware of what our body’s trying to do, the body tries to work with us. We have treated our body as if it was something that we had to contain or control. But the message is that we live in our body. If we treat our body with honour and respect, and our body will serve us well.”

At-A-Glance: How to Stimulate Your Vagus Nerve to Turn ON Your OFF Switch

To help our body “turn on” the vagus to improve its function, there are several social, physiological and physical “tricks” that our body can employ.

- The easiest way to stimulate the vagus nerve is through slow, deep, diaphragmatic breathing that emphasizes the elongation of exhales.

- Singing, humming, or playing a wind instrument also excite this downregulation nerve.

- Massaging areas of the body which are innervated by the vagus alters the vagal tone and provides a relaxation response. These include tolerable pressure to:

- Muscles of face, side and front of neck and head

- Ribcage

- Abdomen

- Positioning the body in ways that compress & decompress areas where the vagus nerve innervates:

- Rocking, which gently oscillates the head

- Neck stretches

- Abdominal & torso rotations that compress and decompress the viscera

- Gently flexing & extending the spine to affect pressure and/or stretch in the visceral area

- Chewing food, sucking on food/objects & gargling

- Safely rubbing the inside of our ear (the bowl-shaped bits, not the ear-canal)

- Positive social interactions

- “Feeling safe in the arms of another” or “Feeling safe in the arms of another appropriate mammal, like a dog,” Dr Stephen Porges

- Meditation & Yoga

Learning how to turn the ON/OFF Switch

Endnotes

- Stanley Rosenberg, Accessing the Healing Power of the Vagus Nerve, (California: North Atlantic Books, 2017), 37.

- Vince, Gaia. “Hacking the Nervous System to Heal the Body.” Discover Magazine, May 2015

- Breit, Sigrid, et al. ‘Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain-Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders’, Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13 March 2018.

- Tracey, Kevin J., “The Inflammatory Reflex,” Nature, 19 December 2002.

- “How Electricity Could Replace Your Medications.” YouTube, uploaded by TEDMED, 26 May 2016.

- Koopman, Frieda A., et al. ‘Vagus Nerve Stimulates Cytokine Production and Attenuates Disease Severity in Rheumatoid Arthritis’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 19 July 2016.

- Porges, Stephen, “The Pocket Guide to the Polyvagal Theory,” (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2017), 15.

- Stanley Rosenberg, Accessing the Healing Power of the Vagus Nerve, (California: North Atlantic Books, 2017), 19.

- Stanley Rosenberg, Accessing the Healing Power of the Vagus Nerve, (California: North Atlantic Books, 2017), 32.

- IMAIOS e-Anatomy online,

- Dana, Deb, “The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy,” (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2018), 4.

- Scudallari, Megan, “Scientists Discover How Vagus Nerve Stimulation Treats Rheumatoid Arthritis,” IEEE Spectrum, 18 July 2016.

- Porges, Stephen, “The Pocket Guide to the Polyvagal Theory,” (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2017), 9.

- Stanley Rosenberg, Accessing the Healing Power of the Vagus Nerve, (California: North Atlantic Books, 2017), 33.

No comments:

Post a Comment