Timothy Hogan

The Holy Grail is generally thought to be one of two things: the cup Christ used at the Last Supper, or the cup which Joseph of Arimathea used to collect Christ’s blood when the Roman soldier Longinus pierced his side with a lance while he was nailed to the cross. These two cups later became conflated both in the Grail literature and the popular imagination.

There are various legends surrounding the cup which Jesus used at the Last Supper.

One has it that it was conserved by St Peter, who brought it to Rome and used it to say mass. It remained in Rome until the reign of Emperor Valerian. In 258, then Pope Sixtus II gave it to his deacon St.Lawrence, who gave it to a Spanish soldier, Proselius, with instructions to take it to safety in Proselius’ native country of Spain. This cup allegedly survives to this day in the Cathedral of Valencia.

The picture above is the chalice, but take note-the relic is only the upper part:

This upper part is a cup of finely polished dark brown agate, which Professor Antonio Beltran believes to be of oriental origin and datable to 50-100 BC.

The account of the chalice’s being taken to Spain doesn’t quite jibe with the account given by the sixth-century Christian pilgrim, Antoninus of Piacenza, who visited Jerusalem in 570 and described a chalice of onyx being conserved as the holy relic.

Approximately one century after Antoninus, the Frankish bishop Arculf toured the Holy Land and described the cup as being two-handled and made of silver, and conserved in a reliquary in a chapel near Jerusalem.

Nothing more was ever seen or heard of these two chalices, and no mention of the relic of the Last Supper appears in the historical record for another five hundred years or so.

Spain again plays a prominent role when the chalice first became the `Grail’: a picture of the Virgin Mary with a `grail’, is possibly the earliest image of a (the?) grail, is in the church of St Clement of Taull, in the Pyrenees, which was consecrated in 1123.

But the first use of the term `Grail’ (Graal) in writing was made by the French poet Chretien de Troyes. His epic poem, Perceval, le Conte du Graal (Perceval, the story of the Grail) was written around 1180 and was the first work of literature to take the Grail as its central theme. In Chretien’s poem, a mysterious vessel or object which sustains life is guarded in a castle which is difficult to find. The owner of the castle is lame or sick and his lands are barren. A young knight (Perceval) happens upon the castle and is invited in. There, he witnesses a mysterious procession but asks no questions. The failure to ask condemns the castle owner and his lands to remain in their condition of sickness and barrenness.

The exact nature of the `Grail’ is not specified in Chretien’s poem, as it wouldn’t be in the magnum opus of one of his principal successors, Wolfram von Eschenbach. The first writer to specifically identify it as the chalice of the Last Supper is Robert de Boron, who wrote his Joseph d’Arimathe sometime between when Chretien and Wolfram wrote their works on the Grail. Nevertheless, the fact that the two most important Grail epics fail to specify what the Grail is – Wolfram suggests that it might be a stone, while Chretien describes it as a light-giving object- are enough to give one pause. why would the Grail be a stone? Why would it give off light? Wolfram uses an unexplained term to designate the Grail- lapis exillis-and claims the story was told him by a certain Kyot de Provence, who had read it in a discarded manuscript he’d found in Toledo, which had been written by a Jewish astronomer. This brings us back to Spain: the Grail was a stone, and legends of it are persistently traceable to Spain and the Pyrenees.

The Grail as a literary subject did not outlast the thirteenth century, so we may well ask: what caused it to appear so suddenly and disappear just as suddenly at this particular moment in history? Oddly enough, the Grail made its appearance- first in painting and then in literature- at around the same time that Catharism, a Christian heresy with deep roots in the Byzantine Empire, came to western Europe. It was particularly prevalent in the south of France- known in French as the Midi-and flourished, then died, at roughly the same time as the Grail legends flourished and then died.

Only when this puzzle is solved can we try to figure out why Wolfram created "lapsit exillis" to describe the grail. Our interpretation of Wolfram’s hidden code requires that we first identify "Kyot", his mysterious informant who is also described as a “Provenzal”. Scholars have tried for centuries to solve this puzzle and always came up with the wrong man. The most common identification is the troubadour Guiot, author of the satire “La Bible”, but he was from Provins near Paris and not from the Provence in Southern France. We started with the numbers 30, 54, 108, and 10 from Plutarch's riddle and Plato's "Timaeus”, which helped us calculate the lifespan of the Phoenix. Wolfram worked from Chrétien's poem, which ends in the middle of a scene, probably because of his death. Although the French master could not fully develop his concept, Wolfram seems to have understood his intentions and interpreted his golden platter as the sun, which he states clearly with the phoenix myth (P.469, 1-12): “These templers...live from a stone of the purest kind. If you do not know it, it shall here be named to you. It is called `lapsit exillis'. By the power of that stone, the phoenix burns to ashes, but the ashes give him life again. Thus does the phoenix molt and change its plumage, which afterwards is bright and shining and as lovely as before." Scholars have come up with all kinds of variations to solve the riddle, Mustard and Passage add in a footnote (3) that "lapis elixir" (as used in one text) "would correspond to the philosopher's stone". The legendary talisman of metallic transmutation is linked to the planets and often symbolized by a hexagram. Hence, if grail and sun are one, it could be a "stone from heaven" of the purest kind, and if the planetary triangles announced Parzival's succession, this symbolism should also appear in other parts of the poem. But we can't dismiss the option that Wolfram's many word inventions might include "lapses from heaven", a plural alternative that suggests a cyclical event. Already the prologue mentions a faith that vanishes like fire in a well or morning dew in the Sun. The most dramatic fusion of the hexagram occurs after the death of Gahmuret's brother, when a knight expresses his sorrow by turning the point of his shield upward, thus converting a watery into a fiery triangle. This shield, the shield of David and Pythagoras, is probably what Wolfram meant when he said the service to the shield is my vocation. It led scholars to the assumption that he was a knight, even a poor knight because he claimed that he was so poor not even the mice had enough to eat. They apparently overlooked that he praised Pythagoras as the most learned man since Adam.

However, according to the Universal Jewish Encyclopaedia (under Magen David), hexagrams were used on tavern signs in Southern Germany during the Middle Ages (4), reputedly because there was a tradition that Pythagorean beggar-monks used it as a secret mark to signal their comrades where they had found a hospitable reception. At left is one of the last remaining tavern signs from Rothenburg-ob-der-Tauber. Wolfram claimed that he was a poor Bavarian from Southern Germany, which leads us to the conclusion that he was not an impoverished knight, as widely held, but a poor Pythagorean monk who served under this protective "shield against hellfire". This adventurous conjecture is supported by Parzival's trance when the fiery and watery triangle is fused in the melting snow and by the poet Gottfried of Strassburg who praised every famous contemporary by name, except for Wolfram whom he criticized for using books of magic without mentioning his name. The clearest reference to the macrocosmic hexagram next to the burning sun is offered by Wolfram when the sorceress Kundrie prophecies Parzival's call to the grail. The scene is well prepared in cosmological terms: Throughout the poem, the poet refers to the planetary positions and their powers (P 454, 17-23, P 518, 5, P 789, 5-7,), as well as to the suffering of the grail king because of Saturn (P 489, 24-28, P 492, 25-30, P 493, 1-8). Finally, with the approach of Mars and Jupiter, the sorceress appears at King Arthur's court and falls to her knees (3), prostrating like Balaam:

To Parzival then she said: `Show restraint in your joy! Blessed are you in your high lot, O crown of man's salvation! The inscription has been read: you shall be Lord of the Grail... Seven stars then she named in the heathen language... And the swiftly moving Almustri, Almaret, and the bright Samsi, She said: Mark now, Parzival: The highest of the planets, Zval, All show good fortune for you here. The fifth is named Alligafir. I do not speak this out of any dream. These are the bridle of the Under these the sixth is Alkiter, the nearest to us is Alkamer.' firmament and they check its speed; their opposition has ever contended its sweep. For you, Care is now an orphan. is shed, that is destined as your goal to reach and to achieve... Whatever the planets' orbits bound, upon whatever their light

In a note, Mustard and Passage (following Wilhelm Stapel) offer the translation of the Arabic names. Hence, the highest planet Saturn, the swifter Jupiter, Mars, and the bright sun all signal the "good fortune" of Parzival. Only then are Venus, Mercury, and the Moon added, which is a clear reference to Plato's "fullness of time" and St. Cyprian's "great conjunction". Earlier, when Kundrie had damned Parzival because of his grave failure at the grail castle (P 312, 20-30), Wolfram featured her knowledge of many languages, of Trivium and Quadrivium (Astronomy). In the following lines (P 313, 14-15) he connected to the Balaam prophecy by saying that her message is "a bridge which brings sorrow over the river of joy".

Parzival as "crown of man's salvation" near the end of the poem and the allusions to the planetary hexagram might be a reference to 6 BCE which connects Parzival symbolically to Christ. But in view of the phoenix and the repetition of the hexagram in 849, Wolfram seems to disprove our hypothesis by falling short of our 854-year cycles. Or is it another riddle?

His "mathematical precision" ends the poem after 827. Could it be a key to 828 CE, suggesting a renewal or new beginning with the conjunction of Saturn and Jupiter, which was followed by a single, planetary triangle with Mars in Leo. Is this a hidden clue to the date when the story begins, the book of Gahmuret, when Parzival is still unborn? Twenty years later the conjunction in May 848 follows, and in February 849 a planetary hexagram appeared in the sky exactly nine months later. This indicates the date of Parzival's birth because Wolfram reveals (5) that Parzival was conceived in May:

April had now passed, and thereafter had come the short, small, green grass - the field was green from end to end – this makes faint hearts bold and gives them high spirits. Many a tree stood in blossom from the sweet air of the May time... Lady Herzeloyde the Queen there surrendered her maidenhood.

If we review another famous clue, Wolframs "eilfte span" (P.128, 29) and consider that he may have worked on this part of the poem in ca. 1215, we could ignore Plutarch's wrong number 30 and subtract "eleven generations" of 33.33 years to reach 848. From Christmas 1214, we actually reach May (1215 - 366.63 = 848.37). Hence, Parzival may have been born nine months after the first conjunction which takes us to early February in 849 when the planetary triangles stood in the sky.

If we apply this calculation to the birth of Christ, 854 years earlier, it seems that he was conceived on May 27, 7 BCE and born as early as December 24/25, 7 BCE, as held by Epiphanius (312-402 CE) who was convinced that Jesus was only in the womb for seven months, or as late as March 21, 6 BC (vernal equinox), as held by Hippolytus according to St. Cyprian. These quotes are from the astronomer David Hughes (6) who follows Ferrari d'Occhieppo (7) by connecting the birth of Christ to the planetary “massings” between 7 and 6 BC. Their focus was the symbolism of Saturn (Jaweh) and Jupiter (Marduk) and the three conjunctions, but neither of them considered Mars and the planetary triangles. It is amazing that we have another two astronomers, who have either never bothered to study Kepler’s "de Stella nova" or simply fallen for Burke-Gaffney S.J. It is unfortunate that Kepler seems to have featured in vain that it is only a "great conjunction" when Mars joins the two highest planets, because it is, according to Cyprian's law, a most perfect great conjunction (8).

The parallels indicate that "Perceval" was born in early 849 and that grail romance connects somehow to the Elijah/John and Elisah/Jesus successions or reincarnations as early Christians like Origen suggested. This could mean that the long-awaited "Second Coming" was overlooked by Christianity in the Middle Ages and obliges us to spend more time with these riddles. Unfortunately, the only way to identify such a Messianic personage in the 9th century, if there was one, is to penetrate the complex allegorical maze of grail romance and solve its riddles. A matter of great controversy, because few scholars consider that grail romance could be based on real events and continue their "wild goose chase" to find King Arthur. They seem to believe that Arthur was real and grail romances the fiction, but we intend to show that the opposite is true

2. Plutarch, de defectu oraculorum, Moralia, Vol. XI, (Harvard, 1927), pp. 381-87.

3. Wolfram von Eschenbach, Parzival, trans. Helen M. Mustard and Charles E. Passage, (New York 1961), pp. 406, 435.

4. Herlitz/Kirschner, Jüdisches Lexikon, Vol. III, (Berlin 1929), p.1282.

5. Mustard & Passage (see above 3.), pp. 54,57

6. David Hughes, The Star of Bethlehem: An Astronomer's Confirmation, (New York 1979), pp. 86/7

7. Konradin Ferrari d'Occhieppo, The Star of Bethlehem, Royal Astronomical Society, (Oxford, Dec. 1978), pp. 517-20

8. Johannes Kepler, Gesammelte Werke, Max Caspar, Bericht vom neuen Stern, (Munich 1938), Vol. 1, p.395

... Repanse de Schoye... has charge of the Gral, which is so heavy that sinful mortals could not lift it from its place.

Finally, as Alexander's gemstone, the Grail is linked with the joys (would that be the meaning of 'Schoye'?) of paradise (p. 125):

Upon a green archmardi she [Repanse de Schoye] bore the consummation of heart's desire, its root and its blossoming -- a thing called 'The Gral', paridisal, transcending all earthly perfection!

In Chrétien de Troyes' Perceval, the Story of the Grail (c. 1190), one of the first works to mention the Grail, it is given no name other than being known as the castle of the Fisher King. As in the later works, the castle is given qualities of Celtic Otherworld (including its invisibility from the outside and seemingly changing locations), as the story's original Grail hero Perceval visits it only when invited and then cannot find it again despite searching for years.

In Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival, based on Chrétien, the Grail castle's name is Munsalväsche (rendering of Monsalvat, in the medieval tradition associated with the name of the mountain Montserrat in Catalonia). There, the castle is the home of a secret society of temple knights who guard the Grail (here a precious stone) from the outside world.

In the Perlesvaus continuation of Perceval, it is called the Castle of Souls but originally was called Eden. The Grail is kept with other holy relics at the castle's Grail Chapel, from which they vanish during the time when the castle is conquered by Perceval's evil uncle.

Corbenic

In the 13th-century Lancelot-Grail (Vulgate) prose cycle, the castle is named as Corbenic for the first time. In the highly Christian mystical Vulgate Quest for the Holy Grail, it is the home of the Grail family from the lineages of Jesus' followers Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, whose history is told in the cycle's prologue, the Vulgate Joseph. The ruler of Corbenic is King Pelles.

As befits the castle of the Grail, Corbenic is a place of marvels, including, at various times, a maiden trapped in a magically boiling cauldron, a dragon, and a room where (depending on text) either an angelic knight or arrows assail any who try to spend the night there. As told in Le Morte d'Arthur, witnessing some of these wonders cause Bors to name it the Castle Adventurous, "for here be many strange adventures" (Morte, Caxton XI). Yet it can also appear quite ordinary: on an earlier occasion, according to the Lancelot-Grail, the same Bors visited without noticing anything unusual. (Perhaps conscious of this apparent contradiction, T.H. White in his modern The Once and Future King treats Corbenic as two separate places: Corbin is the relatively mundane dwelling-place of King Pelles, while Carbonek is the mystical castle where the climax of the Grail Quest takes place.)

Corbenic has a town and a bridge which Bromell la Pleche swears to defend against all comers for a year, for love of Pelles' daughter Elaine (Morte, Caxton XI-XII). It is on the coast, or at least is mystically moved there for the purposes of the Grail Quest: Lancelot arrives at Corbenic by sea at the climax of his personal quest. Corbenic's seaward gate is guarded by two lions, aided by either a dwarf (Morte, Caxton XVII) or a flaming hand (Lancelot-Grail). Lancelot's arrival results in his and Elaine's conception of Galahad, the new Grail hero of the prose cycles.

It is unclear whether Corbenic is to be identified with the castle inadvertently levelled by Balin when he delivers the Dolorous Stroke upon King Pellam in the Post-Vulgate Merlin (Morte, Caxton II); if so, then Corbenic is in Listeneise (and is presumably rebuilt at some point). The Lancelot-Grail gives the name of its kingdom only as of the Land Beyond.

Cor-beneic: 'Blessed Horn' and 'Blessed Body'

Helaine Newstead and Roger Sherman Loomis have presented a convincing case for the origins of the name Corbenic in a myth concerning a type of Welsh cornucopia - to wit, the horn (of plenty) of Brân the Blessed, a magical, food-providing talisman. The argument hinges on confusion resulting from two possible meanings for the Old French li cors (a nominative case form) which can mean both 'the body' (Modern French le corps) and 'the horn' (Modern French la corne), leading to the mistranslation, by Christian authors, of li cors beneit as the blessed body - the latter readily construed as a reference either to the body of Christ or to the body of a saint preserved as a holy relic. The common scribal error of misreading the letter 't' as a 'c' yielded the second element -ben(e)ic. The original name of Castle Corbenic can thus be reconstructed as Chastiaus del Cor Beneit - the Castle of the Blessed Horn (of Brân) - subsequently misunderstood to mean the Castle of the Blessed Body (of Christ). The origins of the maimed Fisher King, master of the Grail Castle of Corbenic may be found in the maimed King Brân the Blessed, whose story is told in Branwen ferch Llŷr, second of the Four Branches of the Mabinogi.

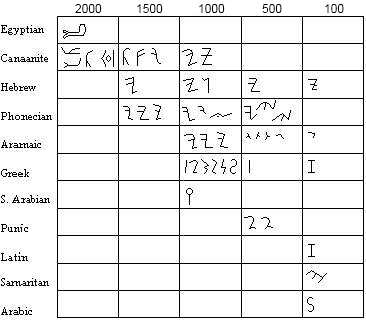

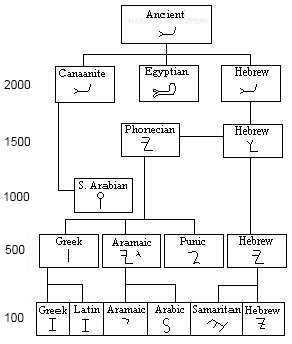

The Phoenician letter gave rise to the Greek Iota (Ι), Latin I, J, Cyrillic І, Coptic iauda (Ⲓ) and Gothic eis ![]() .

.

The term yod is often used to refer to the speech sound [j], a palatal approximant, even in discussions of languages not written in Semitic abjads, as in phonological phenomena such as English "yod-dropping".

Origins

Yodh is originated from a pictograph of a “hand” that ultimately derives from Proto-Semitic *yad-. It may be related to the Egyptian hieroglyph of an “arm” or “hand”

Hebrew Yud

| Orthographic variants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Various print fonts | Cursive Hebrew | Rashi script | ||

| Serif | Sans-serif | Monospaced | ||

| י | י | י | ||

Hebrew spelling: יוֹד; colloquial יוּד

Pronunciation

In both Biblical and modern Hebrew, Yud represents a palatal approximant ([j]). As a mater lectionis, it represents the vowel [i]. At the end of words with a vowel or when marked with a sh'va nach, it represents the formation of a diphthong, such as /ei/, /ai/, or /oi/.

Significance

In gematria, Yud represents the number ten.

As a prefix, it designates the third person singular (or plural, with a Vav as a suffix) in the future tense.

As a suffix, it indicates first person singular possessive; av (father) becomes avi (my father).

"Yod" in the Hebrew language signifies iodine. Iodine is also called يود yod in Arabic.

In religion

Two Yuds in a row designate the name of God Adonai and in pointed texts are written with the vowels of Adonai; this is done as well with the Tetragrammaton.

As Yud is the smallest letter, much kabbalistic and mystical significance is attached to it. According to the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus mentioned it during the Antithesis of the Law, when he says: "One jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the law, till all be fulfilled." Jot, or iota, refers to the letter Yud; it was often overlooked by scribes because of its size and position as a mater lectionis. In modern Hebrew, the phrase "tip of the Yud" refers to a small and insignificant thing, and someone who "worries about the tip of a Yud" is someone who is picky and meticulous about small details.

Much kabbalistic and mystical significance is also attached to it because of its gematria value as ten, which is an important number in Judaism, and its place in the name of God

|

| Ancient Name: | Yad |

| Pictograph: | Arm and closed hand |

| Meanings: | Work, Throw, Make, Praise |

| Sound: | Y, iy |

History & Reconstruction

The Early Semitic pictograph of this letter is  , an arm and hand. The meaning of this letter is work, make and throw; the functions of the hand. The Modern Hebrew name yud is a derivative of the two-letter word

, an arm and hand. The meaning of this letter is work, make and throw; the functions of the hand. The Modern Hebrew name yud is a derivative of the two-letter word

became the

became the  in the Middle Semitic script. The letter continued to evolve into the simpler form

in the Middle Semitic script. The letter continued to evolve into the simpler form  in the Late Semitic script. The Middle Semitic form became the Greek and Roman I. The Late Semitic form became the Modern Hebrew י.

in the Late Semitic script. The Middle Semitic form became the Greek and Roman I. The Late Semitic form became the Modern Hebrew י. |

|

No comments:

Post a Comment